Tomtit and Pushkin

Tomtit and Pushkin is a series of ten educational films devoted to major problems of studying Russian in grades 10 and 11 in Russian and foreign schools. Masterskaya created this series for St. Petersburg State University to be posted on the Russian@edu website launched by the Pushkin State Russian Language Institute in 2014.

1. Team

St. Petersburg State University, commissioned by

The Pushkin State Russian Language Institute

Production

Masterskaya

Screenplay

Sergey Monakhov

Text

Dmitry Cherdakov

Cinematographer, Editor

Evgeny Evgrafov

Director

Aleksandr Seliverstov

Art Director

Dima Barbanel

Designer

Denis Zaporozhan

Animation Designer

Alexey Astafyev

Music

Dmitry Evgrafov

Illustrator

Sergey Kalinin

Modeler

Boremir Bakharev

Typefaces

Anton Terekhov

Konstantin Lukyanov

Executive Producer

Irina Zhuravleva

Actors

Stanislav Malyukov

Mikhail Belov

Makeup

Alexey Graf

Narrator

Konstantin Terentyev (for films 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 9)

Petr Bukharkin (for films 5, 7, 8, 10)

Props

Igor Khilov

2. Idea

Our idea was to create such educational films about the Russian language for high school students that no one in Russia had ever made before. We had to write an interesting text and a bold screenplay, capture the enchanting beauty of St. Petersburg in the fall, find inspired actors, arrange stunts, draw two- and three-dimensional animation, create unexpected visual effects, compose an original score, and design typefaces. In a word, everything in these half-an-hour films had to be done in such a way that children and their parents would be glued to the screen, listening to the story of the most interesting and important aspects of the Russian language.

Waking up at the cemetery. — A leaf, another leaf. — Bag man brews unbagged tea. — Tomtits falling from a tree. — Where do I finally bury all this? —Backward, time, and forward! —A meal from ashes. — Pushkin digs a grave. — A lot of elderly women and flashbacks. — The spade’s deadly hit. — A plague doctor.

3. Solutions

3.1. Title sequence

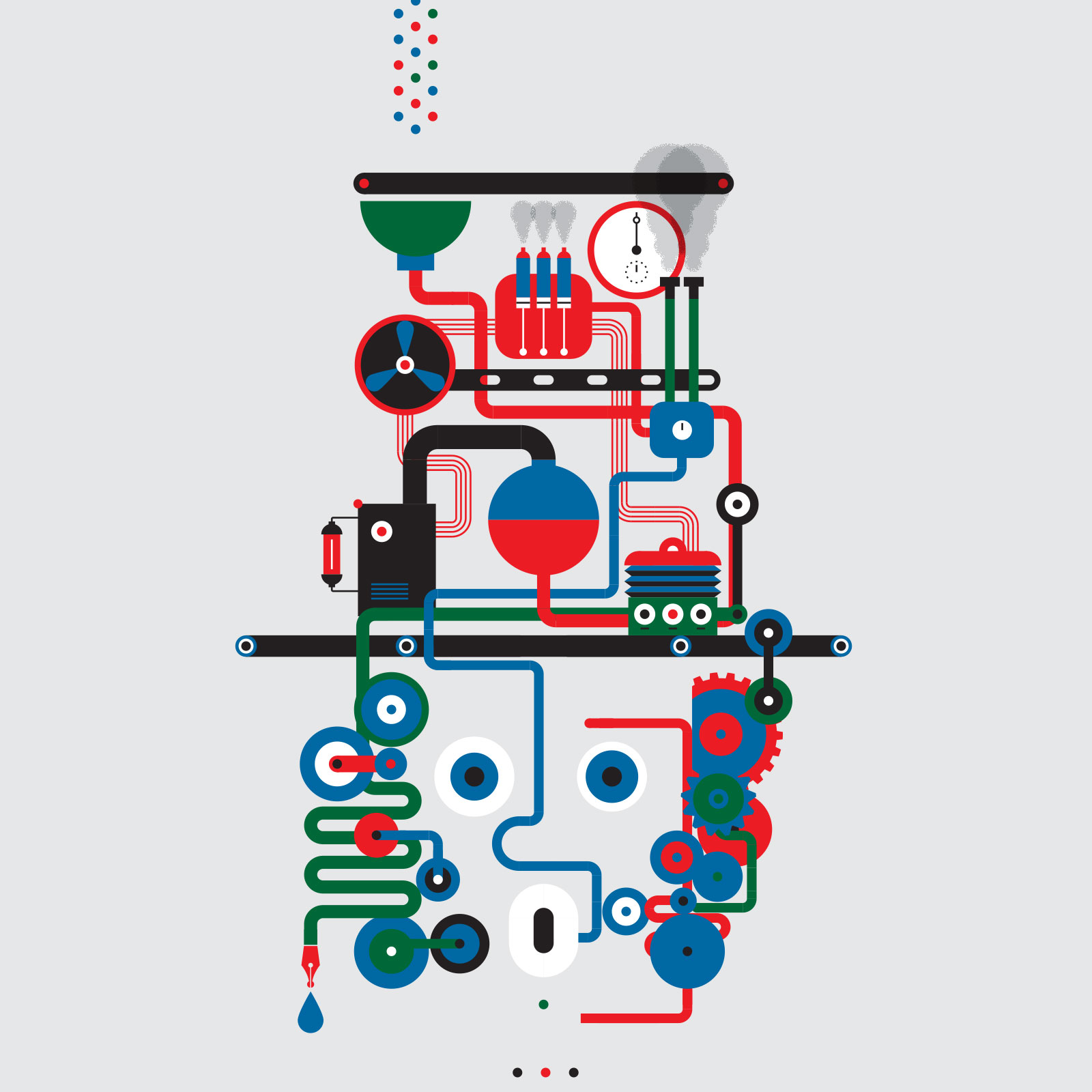

The title sequence is common for all films in the series and is an animated scene with its own composition. Pushkin’s head (he is the main character of the series) is shown as a steampunk machine which consists of cubofuturistic parts and symbolizes the language and the logic of word formation. The title of each film comes out of Pushkin’s head as if generated by it: the machine produces letters with steam and noise; at first, the letters are crooked and uneven, then they jump to the right places in the line, while little hammers and presses shape them to be graphemes. The steampunk machine head is also an allegory of the language norm. It closely watches the carefree Pushkin when he takes a walk across Palace square.

Alexey Astafyev:

Illustrations created by Sergey Kalinin required a specific technique; it is called shape animation. Pushkin’s head appears on the screen in a particular order: first, dots pop up out of nowhere, then they form lines, and we begin to recognize eyes and a nose and then sideburns, which go down the left and the right side. This is how the image is being built. After that, Pushkin gets a top hat; however, his face is still in motion: the mechanism is moving and its parts continue to interact until the end of the clip. We animated the entire Russian alphabet for the title sequence; for each letter we designed phases of its appearance on the screen, the whole life cycle; the only thing left was to connect these phases so that the process of transition from one state to another would look smooth and natural.

Pushkin and a horse. — The Prague Linguistic Circle. — How to cross Palace square and make everyone hate you. — The flight of the flaming Tomtit. — Everything flows, nothing changes. — Acrobatic sketches, a scared girl with pins. — The poet and the crowd. — Pushkin gets into a carriage. — Pushkin in the carriage. — “I’m gonna punch you...”

3.2. Stop motion animation

Tomtit is one of the major mysteries of the series. (This character originated in the Russian language textbook for grades 10 and 11, designed by Masterskaya, and was brought to life in the films.) Why does Tomtit always follow Pushkin? How are they connected? Why does Tomtit often dress up like Pushkin? Can Pushkin catch Tomtit? Unfortunately, most of these questions remain unanswered.

Alexey Astafyev:

The animation of Tomtit is an entirely different genre than that of the title sequence. According to the plot, this three-dimensional character had to be a part of the scenes shot by Evgeny Evgrafov, just like other actors. We thought of various ways to create Tomtit. Since in the beginning of the project the original reference was to a Czech wooden toy, we decided to do it through stop motion animation. The wonderful puppet designer Igor Khilov made Tomtit in five days, and then, in three days, Evgeny and I shot twelve scenes with it. It turned out to be a nice story, even closer to the author’s idea than the original three-dimensional animation. You can feel that the wooden toy has its texture, it is roughness, and you see that it is alive.

Evgeny Evgrafov:

It was awesome. Dima locked us up in his storage room with Land Rover Discovery summer tires for three days and told us not to leave until we create the animation. He brought us food from time to time. It was the first time I created stop motion (apart from filming animated Lego figures with my son), and to be honest, I was not completely sure we would create such a balanced and lively alternative to 3D. I have to apologize to Alexey for this.

Dima Barbanel:

Nevertheless, Tomtit’s anatomy is extremely simple: wings (wingbeat, wingspread), a tail (in two positions), a head (in two positions), a beak (open and closed as if it is speaking), eyes (open, closed, and turned to the side), feet (it can walk), and a neck (can be tilted).

Several hundred thousand. —Bears. — A scary ogre with a donut. —Let’s speak properly! or Monkey Language. — Let me understand you. — Pushkin’s pursuit of a hot dog. — The riding circle: being nervous around horses. — Should I get dressed or get a dress?.. — Caged.

3.3. Two-dimensional animated segments

Each episode in the series contains its own “film inside the film” divided into several parts that are equally distributed through the episode and are related to the main story line. All these black-and-white segments of two-dimensional animation follow the same pattern: short funny moments from Tomtit’s life and the scrolling text of Pushkin’s letters to his family and friends. Sergey Kalinin’s animated illustrations contrast sharply with the video and the peculiar epistolary style of the early 19th century, which adds to the absurdity of what is happening on the screen.

Krylov monument. — Petrify! —Tomtit wiggles its tail. — New Pygmalion and Galatea: what was covered by the blanket? —Many Pushkins in the park. — A plate, a glass, a mouse — all shattered. — Herring, dear friend. — Why you cannot catch a child with a poker. — Flour.

3.4. Compositing

Alexey Astafyev:

This part is mainly technical; it included the tracking of scenes shot with a hand-held camera, rotoscoping in some cases, and in others, animation of infographics and other graphic elements. You can’t really call this work creative, it is more technical. And there was a lot of it! Denis Zaporozhan created illustrations and infographics for the animation.

Poems at the training grounds. — Chronotope drowns. —Crouching Pushkin, hidden beaver. — Inventory this! — The fall off an armchair from different angles. — And the beaver flies, and flies, and flies... — Jacob’s spiral staircase. — A whisper, a sigh, a drill. — 138 ways to cook...

3.5. Music

Dmitry Evgrafov:

During the prototyping stage, we agreed that in terms of sound the process of assembling the elements of Pushkin was entirely mechanical, a direct reference to steampunk. However, it was necessary to introduce a tone, which would rise over the mechanical part and create the supreme harmony of the clip, so that the title sequence would unite the whole series.

The first iteration

I wanted to make it sound mechanical but also have a strong tonal part. I thought that a noisy presentation would not sound well together with the music of the narration that follows the title sequence. I had this idea stuck in my head that Pushkin is being assembled from parts, like the Frankenstein monster. Another thing that I liked was that such music could be described as “strange but interesting”. The result was strange but not exactly what we needed. Now I realize that I got carried away with playing with unusual chords and atonal notes, although the texture of the music and the rapid change of harmonies did not really relate to the picture.

The second iteration

I decided to start again after Dima Barbanel’s feedback, “sounds appear gradually... and form a spontaneous, partly dodecaphonic phrase. And only when Pushkin’s image is complete, the sounds become a tune, a mode, an integral composition.” I was really inspired by this approach, because previously I had been studying a specific part of the 20th century classical music where atonal structures, dodecaphony, clusters, and unusual playing techniques were used. Why? Because it sounds awesome; and besides, who said that music has to be 100% comfortable? Having decided on the frame, which was about half done, I sent the result to Barbanel to see what he thought. Long story short, we came to a conclusion that this approach lacked cordiality and that at that stage it was just a set of technical sounds following the movements on the screen.

The third iteration

I decided not to modify the second version and just start from scratch again. The only thing I took from the second version was the way the usic was “opening”: one chord basically begins with a note, then it enriches dynamically, more instruments are used, but it is still just one chord, up to the point when Pushkin is assembled — and then it turns into something bright, with a tune and all the bells and whistles. Between my second and third iterations, I made a trip to St. Petersburg, where the films were being shot; this helped me to create a clear image of what intonation should be the core one. Of course, that was an anthem. However, when Dima heard it, he said that it resembled Kultura TV channel, it was not clear, and that we had to think it over more thoroughly. Now, looking back, when I compare that version and the final one, I realize that it was obviously not complete and not good enough.

The fourth and the fifth iterations

In the last two iterations the initial version got a daring bass, a fresh arpeggio, and juicy chords played on an analog keyboard. It allowed us to transform frail attempts into lively beats, which can be heard in each film and which create the necessary mood for all of them.

There, by the billows desolate. — A half of a blue woman. —Sand Sculpture Festival. — A man kicks another man in the ass. — Pushkin and a treacherous net. — A ravelin of the Peter and Paul fortress. —Eyes of an owl. —Three, seven, ace, or Your queen is dead. —The Monte Cristo method...

3.6. Screenplay

Sergey Monakhov:

Writing the screenplay was both easy and difficult. It was easy mainly because I kept telling myself “Whatever you come up with, it is going to be better than a traditional educational film with teachers’ talking heads and a blackboard which is constantly blocked by Power Point slides.” On the other hand, it was hard because I had to write the screenplay without the most essential part, the narrator’s text (which had not been created by then; we only had the bullet points.) Besides, while the first five scripts were created in a more or less conventional work environment, the last five of them were written during short stops on the way from Moscow to Sochi and back. I am afraid it affected their quality.

Before we started, Dima Barbanel and I agreed upon some basic principles:

1. Each film is shot in different locations in St. Petersburg. (Initially, the location list included quite exotic places like an Auchan parking lot and so on, but later we decided to use more traditional ones, like The Peter and Paul Fortress, The Summer Garden, Palace square; although one scene was shot in a horrible abandoned plant in the Kupchino district, and another one at the Udelny market in the middle of the day, and the crew were nearly robbed.)

2. Pushkin is played by an actor who does not say a word, but who walks, looks around, and in some situations interacts with passersby. (Then, like in the history of Greek tragedy, we needed a second actor, then a third one, etc.)

3. All the texts in the films are narrated by the same person, who would not appear on screen. (We ended up having two narrators, one of whom had considerable speech impediments.)

4. To illustrate some ideas from the narrator’s text we would impose some short phrases and images on the video, like in Sherlock TV series. (As a result, we thought of 10–12 completely different gimmicks; it is a pity we were not able to use all of them.)

You can say that the plot of each film represents its genre stereotype: there is an action film, a mystery thriller, a love story, a film noir, an Eastern fairy-tale, and a reality film. However, certain signature elements of these genres float like shipwreck in the sea of total absurd. Pushkin fights with a beaver. A bag man brews tea at a cemetery. Dozens of Tomtits come out of a carelessly thrown top hat. A dwarf in a turban sells a backpack at the Udelny market. The upper body of a busty blue woman flows away on a piece of cardboard down the Neva river.

Overall, the series turned out to be quite diverse. Sometimes too long, sometimes elusive, sometimes bright, sometimes imprecise, sometimes cheesy, and sometimes thoughtful. But I am sure the audience is not going to be bored. Moreover, the noble narration, which was imposed on this visual chaos, creates a complete illusion of studying Russian in your sleep, as if the lecture is recorded directly into your brain, past the sense organs.Gas station king. — Abandoned hell. — Characters of the everlasting dream. — Glagolitic and Cyrillic — The first appearance of the ghost. — A turtle at night. —Who ate from my bowl? — How Pushkin called Pushkin. — Here bricked—so Nature gives command—Your window. —...

3.7. Actors

Sergey Monakhov:

Our casting had just one task, to find an actor who could play Pushkin immersed into the current Russian reality and used to it. We almost immediately thought of a candidate, although I cannot say it was an obvious choice. We invited the FC Zenit mascot, a blue-white-blue lion, whom Dmitry Cherdakov and I knew very well since we saw him at the Petrovsky stadium. I mean, not the lion, but the man who plays the mascot and amuses spectators, Stas Malyukov from the Upsala circus.

After that, we had to create the image and find an appropriate costume for our character. Dima Barbanel sent us several photos by the popular Daedalus for reference; these pictures were really good. Stas and I took them to the Kapussta costume studio, where they gave us a pair of more or less classic pants, a dusty frock-coat, a couple of not very clean shirts, a top hat, an extremely heavy macfarlane coat, and a plastic cane with an aluminum knob. Dima saw the pictures and said, “We need splendor, not a guiser who poses for photos with passersby near a zoo.” And Evgeny Evgrafov added that clothes probably would not help our character; still, just in case, he advised us to shop at Uniqlo, then at Topman, and a little bit at H&M.

However, we decided to give up splendor in favor of Stas’s artistic skills, suppleness, and flexibility of a circus performer. And I believe it was a good move. Moreover so since Stas’s friend Misha Belov followed him into the project as the second actor; he played brilliantly in several different supporting roles.

Pushkin as an owner-driver. — A new Evgeny apprehending floods. — An unknown woman in black does a plie. — Rules of transporting women in a car trunk. — A sightseeing tour around memorable Pushkin sights. — The Tomtit monument design competition. — Nur haben oder sein. —The duel. —Underground.

3.8. Principal photography

Evgeny Evgrafov:

When Dima Barbanel first told us about this project, everything was subdued and unclear, but as we were getting closer to shooting, the main idea, the plot and the visual language were becoming clearer.

Initially, it was a low-budget project, which meant that we would have to use the most effective and cheap solutions. It took a lot of effort on my side to convince the guys not to put a GoPro on Pushkin’s top hat. We agreed that all the filming had to be done with a hand-held camera with a wide angle, but it had to be a professional camera. Such an approach can add vivacity and a personal touch, as if the audience were really there and took part in saving the Russian language. Besides, it helps to shoot quickly. It was important since in St. Petersburg there are only eight daylight hours in late October.

Every movie begins with a screenplay; when Sergey Monakhov began to send the texts of the first films, all crew and cast became a bit anxious. Those were not trivial educational videos; in fact, they were short films with a large number of scenes, characters, and props. At this stage, a lot was done by Ira Zhuravleva; it was only because of her incredible, magical efforts that we managed to fix up all the sets in a week, though it usually takes months.

All scenes were shot with a Blackmagic camera; it is easy to use and maintain, and thanks to that we could get beautiful views despite the unpredictable and constantly changing weather, typical for St. Petersburg in the fall: grey sky, clammy fog, shiny orange leaves, bright contrasting light at the square and on the beach, rain mixed with snow, which makes camera lenses steam up, poor artificial lighting of the palace and casemates, the dark abandoned building in Kupchino, dark night at the Chernaya River, and sharp glistening knives at the Udelny flea market.

I have a favorite scene in each film; the main character may not be in all of them, but these scenes always convey the mood, which we thought was as important a message as education. Despite all the challenges, there was a lot of laughing and joking behind-the-scenes. In fact, we found Sergey’s script so absurd and witty that we were laughing almost all the time; I would like to thank him for managing to combine beauty and sense.

Each day brought about moments that make you want to live and grow further to experience them again in the future. This kind of work is not routine; it is a creative process everyone is engaged in. When the principle photography is over, you understand how awesome it was and how you are going to miss all these people, their smiles, the joy, short moments of despair and, shortly after, breakthroughs that overcome the narrow human mind.

Aleksandr Seliverstov:

I remember clearly what I felt when I read the script of the first film which Evgeny Evgrafov had sent me. “Total madness,” I thought and immediately began writing the director’s vision of how we can put it on the screen. I was impressed by the fact that such a script, full of creative ideas and non-trivial plot twists, which resemble Daniil Kharms’s works, could appear in a state-funded project. To think about it, in cinema terms, it is a pure art film. I could not imagine it was possible. Luckily, some things life brings about can still surprise me. Now the project is finished, and it turned out just as we had planned it to be.

I have to say that the screenplay and the scheduled amount of work per day (more than twenty minutes) dictated the manner of shooting. Especially if you bear in mind that we had only eight daylight hours. In reality, there was only one way: each scene had to be filmed in one shot, except the rare situations when it was not physically possible.

In general, I love improvising, and of course, there was plenty of it: a lot of scenes were created on the set, and I am extremely glad that most of them made it to the final cut. We had it all: long contemplative shots which would do honor to Carlos Reygadas; absolute nonsense in a wide shot, as if created by Roy Andersson; a poetic glance inside the human soul, inspired by Hong Sang-soo; scenes that remind you of Buster Keaton movies; scenes that resembled the Russian Maski sketch show, and super-action stuff like the Crank movie with Jason Statham.

A white-faced dwarf with red ears attacks. — What is to be done and who is to blame for such large ears? — i. A hot water washbasin and washing powder. — ii. Lots of cabbage. — iii. Pushkin juggles with fruit, or The Death of Tomtit. —Freedom...

3.9. Typefaces

Dima Barbanel:

The ideas of the title sequence and the typeface were synonymous: it was a visual story about the incredible creation of everything from nothing. This process does not follow the linear formation principle that we are used to, it is inconceivable. The typeface that we were going to design had to lose its historical background, stop being a grapheme connected to the concept and the word at any moment of its development throughout centuries, up to the point where it became abstract and not related to the structure of any character. As the plot was unfolding, the grapheme had to be irrationally assembled from elements, which often did not come naturally together in a row of successive transformations. The typeface by Konstantin Lukyanov was based on the Berhold Grotesk remake, which we had done for the VDNH project. The version has a limited set of characters, capital letters, numbers, and a set of alternative characters, from five to twenty of them, depending on the grapheme.

Konstantin Lukyanov:

The Pushkin typeface is a rhythmic discovery. Its shapes seem to be limited to one width, but when they overcome it, they develop. It conveys the idea of motion, cinema, and screen. It was also an exciting challenge to create multiple additional characters, patterns, decor; everything that developed the typeface as a visual abstraction.

Gradual transformation. —People should be beautiful in every way, including their top hap and sideburns. — Pushkin’s irritation indicator. — O, laugh, laughers! — The top hat is cast. — So this is what you are, a magician’s hat! — Poet wanted. — A pie and the solar disc. — Tomtits will find you.